By Laura Thornton

As Brayden snowboarded down Oregon’s Mt. Bachelor on February 20, 2018, he was already enjoying a little taste of the kind of success that comes only with many hours of hard work.

Just 11 years old, he’d recently won the under-13 division of a surfing contest in his hometown of Laguna Beach, California, and was looking forward to going pro. A surfer through and through, he’d taken his skills to the slopes that day, and with each trip down the trail, he aimed a little higher on the jump. That’s the kind of young man Brayden is—always working hard to get better.

But after he landed the last jump of the day, he fell down. “When I caught up to him, he was just lying there, lifeless,” says his dad, Matt. “His eyes were in the back of his head. No pulse. No breath. If I didn’t give him CPR, he could have died.”

A rescue team airlifted Brayden to a nearby hospital, where he remained in a medically-induced coma for three weeks, his brain badly injured from the fall, his body paralyzed from the neck down. Doctors cautioned that the paralysis could be permanent. But Brayden wasn’t giving up without a fight, and soon began the long process of relearning how to talk, eat, walk and use his arms and hands.

“He’s very dedicated to whatever he does,” explains his mom, Denise. “He is a hard worker. Give him a push, and he just keeps going.”

Brayden spent four months in inpatient rehabilitation in Oregon, then went home and began outpatient therapy, sticking with it like any athlete determined to win. His walking improved, as did the use of his left arm, but his right arm remained immobile.

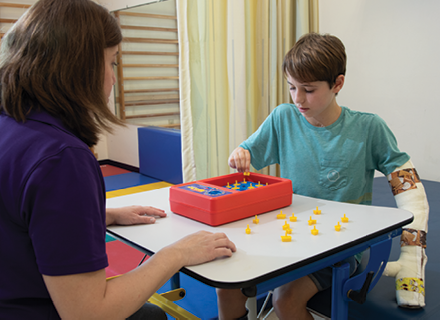

Suspecting dystonia, which can result from a brain injury, his parents brought him to Kennedy Krieger Institute for constraint-induced and bimanual therapy (CIBT), in which the stronger arm is put in a hard cast—shoulder to fingertips—during therapy, forcing the weaker arm to fully engage in therapy exercises. It’s just one of the many types of therapeutic treatments for which Kennedy Krieger is well known.

The Right Diagnosis

During Brayden’s initial evaluation at the Institute, occupational therapist Lindsey Harris noticed that Brayden’s right shoulder was completely frozen. With dystonia, there would have been at least some movement—it just wouldn’t have been controlled.

It turned out that in the snowboarding accident, he’d fractured one of the bones in his shoulder, as well as his wrist, probably from landing on his outstretched arm, Harris explains. That had gone undiagnosed, and scar tissue had healed over his shoulder joint, a condition called adhesive capsulitis, keeping his right arm from benefiting from therapy.

Surgery with Johns Hopkins pediatric orthopedic surgeon Dr. John Tis would be needed to free Brayden’s shoulder joint, but “I don’t care how big the needles are,” Brayden said. “I promise, when I wake up, to give everything I have and 110 percent on my rehab.”

After the surgery, Brayden completed three to five hours of intense therapies a day for nearly three months at Kennedy Krieger’s day hospital, part of the Institute’s Fairmount Rehabilitation Programs, rehabbing from both the surgery and the brain injury. This past summer, Brayden returned for two more months of daily rehabilitation at the day hospital.

Comprehensive Rehabilitation

Over the course of the two admissions, Brayden improved his balance and overall strength, and his ability to walk and use his arms, especially his right arm, with which he did CIBT during his second admission. Active video games had Brayden doing things like playing virtual tennis on one foot to work on his balance. Harris got out a scooter board, so Brayden could mock-surf down the hall.

|

|

|

|---|

Vestibular testing revealed that Brayden was having difficulty focusing on a target during activities that also required head movement. This was impacting his balance as he walked, says physical therapist Dr. Katlyn Billups. To retrain the connections between Brayden’s eyes and brain, Dr. Billups would hold up a card with a smiley face on it, and Brayden would shake his head while keeping his eyes on the face.

“Initially, he could only do five to 10 seconds of that, but by the end of his second admission, he was able to keep it up for a minute,” Dr. Billups says.

Brayden’s rehabilitation addressed more than just movement. Speech-language pathologist Brynn Schor helped Brayden redevelop his memory. To help him recall words, Schor encouraged him to describe the word he was trying to remember. Together, they worked on strategies to help Brayden break down complex sentences and directions, and problem-solve.

Every time Brayden goes to Kennedy Krieger, he just gets stronger and stronger, improving by leaps and bounds. It's an amazing place.”

– Denise, Brayden's mom

Between therapy sessions, Brayden worked with educational specialist Alecsandra Adler, who discovered that Brayden did well in a small class setting, with plenty of breaks and specific strategies to help him concentrate. Adler prepared recommendations for an individualized education plan for Brayden’s teachers to follow to ensure he would continue to succeed in school.

And neuropsychologists Dr. Natasha Ludwig and Dr. Danielle Ploetz worked with Brayden to develop a list of strategies—e.g., “calm down,” “take a break”—that he could use when he felt frustrated. At first, he needed cues to use the appropriate strategy, but by the end of his second admission, he knew exactly when and how to apply them.

Since returning to California, Brayden’s kept up with therapies, both at home and with a local physical and occupational therapy provider, where he goes four times a week. “Thanks to all the therapy he’s done, he’s able to hang out at the beach with his friends again,” his mom says.

Of course, what he really wants to do is surf. And with Brayden’s determination knowing no bounds, Laguna Beach may not have long to wait before seeing him take to the waves again.

|

Visit the Day Hospital and Constraint-Induced and Bimanual Therapy Program pages to learn more about therapy services at Kennedy Krieger. |

|---|