By Laura Thornton

It’s 1988, and Dr. Gary W. Goldstein, Kennedy Krieger Institute’s new president and CEO, is taking a walk through the four floors of the Institute’s only building. He wants to get to know the place a little better.

He quickly meets up with an 8-year-old boy walking away from his mom and physical therapist. The boy is smiling, excited and very happy. His mom and therapist are crying.

“What’s happening?” Dr. Goldstein asks.

“This is the first time my son has ever walked,” the boy’s mom answers through tears of joy.

Throughout his 30 years at Kennedy Krieger, Dr. Goldstein has never forgotten that boy. The children at the Institute are always foremost in his mind, guiding just about every decision he makes on the job.

“Any time he talks about research at Kennedy Krieger, he starts by talking about the children who are living with a serious or rare disease—the children we want our research to help,” explains Dr. Amy J. Bastian, the Institute’s chief science officer. “He always puts the children first.”

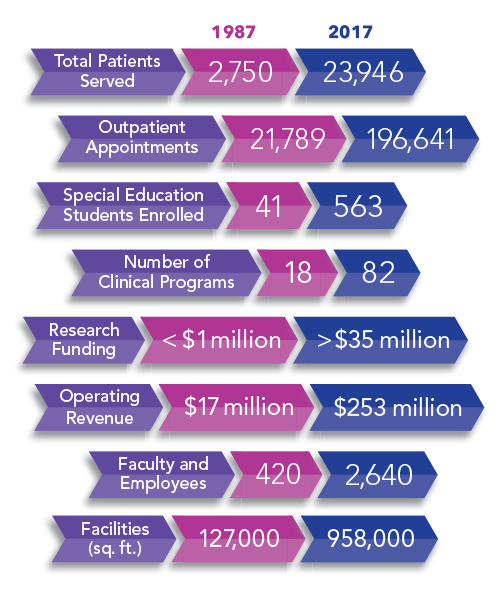

When Dr. Goldstein began at Kennedy Krieger, the Institute was seeing about 2,750 patients a year, and educating about 40 elementary school students. Eighteen outpatient programs offered patient services, and the Institute employed a little more than 400 people.

Today, as Dr. Goldstein prepares to step down from his current roles at Kennedy Krieger, the Institute sees about 24,000 patients a year and educates close to 600 students, from preschool to postsecondary vocational training. It diagnoses and treats hundreds of diseases of the brain, spinal cord and musculoskeletal system; offers 82 outpatient programs; provides services at multiple locations; and runs three school campuses. More than 2,600 employees now work at the Institute, while hundreds of doctors, therapists, nurses, researchers and teachers receive training at the Institute each year.

The extraordinary growth of the past three decades means more children than ever before are receiving the medical, therapeutic and educational care they need. Guiding that growth has been Dr. Goldstein.

A Visionary

“It was an easy choice,” selecting Dr. Goldstein as the Institute’s sixth president, says Michael J. Batza Jr., a board member for the past 38 years, board chair at the time Dr. Goldstein was hired, and a member of the committee that selected Dr. Goldstein.

“We chose the absolute best person for the job.”

“Gary is a visionary,” Batza adds. “He’s always looking forward—that’s his greatest contribution to the Institute.”

“The first thing Gary did was the opposite of what many new executives do,” recalls Dr. Michael F. Cataldo, director of the Institute’s Department of Behavioral Psychology and a Kennedy Krieger employee for the past 40 years. “Instead of changing things, he listened.”

His new co-workers told him they needed more space for their work. The four-story building wasn’t enough. The elementary school occupied just a few rooms on the second floor, and its teachers constantly worried about how their students would fare in mainstream middle schools. The research labs, outpatient center, inpatient hospital and administrative offices were bursting at the seams.

Within a year, Dr. Goldstein had orchestrated the Institute’s first expansion: Just as he was securing a substantial donation to the Institute from Zanvyl Krieger, a Baltimore businessman and Institute board member, a large city school building went on the market just three blocks away. Two weeks later, thanks to that donation, the building was part of the Institute. And that was just the beginning—more than half a dozen major buildings have become part of Kennedy Krieger over the past 30 years, giving researchers and clinicians room to expand their work.

“Our long-range plan was never about building buildings,” Dr. Goldstein explains, “but about expanding programs, with a balance between research, school and clinical care.”

“Gary is an extremely honest, humble and self-effacing leader who cares deeply about the Institute’s employees, work and mission. He’s also a brilliant scientist and an excellent physician and pediatric neurologist. He really has been the perfect person to have led the Institute for the past 30 years.”

– Dr. Michael V. Johnston, executive vice president and chief medical officer for Kennedy Krieger Institute

The Right People

“Gary’s other great contribution has been his ability to recruit, motivate and retain key individuals,” Batza says, “which isn’t always easy in such a creative and diverse, complex environment like Kennedy Krieger.”

Dr. Goldstein’s management approach has been the opposite of that of many institutions: After recruiting the best people for key leadership positions, he’s encouraged them to develop programs following their own instinct and initiative.

“Thanks to Gary, we function very differently from about 99.9 percent of nonprofits, and that works to our advantage,” explains Jim Anders, the Institute’s executive vice president and chief operating officer for the past 30 years.

“He’s essentially allowed people who were already highly capable of acting entrepreneurially to do just that, without a whole lot of restrictions,” Dr. Cataldo says, “as long as the evidence is there, showing they’re making progress.”

The result is “an innovative, open environment where people can really optimize their skills and passions,” says Dr. Harolyn M.E. Belcher, director of the Institute’s Center for Diversity in Public Health Leadership Training.

And “Gary is always looking for opportunities to connect people,” adds Dr. Bastian, whom Dr. Goldstein recruited in 2001. “When you’re focused so intently on your own research, it’s easy to feel boxed in, and it can be hard to make the connections you need to further your research. But that’s where Gary comes in—he’s really good at making those connections.”

Groundbreaking Research

“Undergirding everything has been the philosophy that if we really want to improve the lives of children with disabilities, we’ve got to do research,” says Dr. Nancy S. Grasmick, co-director of the Institute’s Center for Innovation and Leadership in Special Education, and member and rising chair of the board. When Dr. Goldstein began his tenure at the Institute, research funding was only around a million dollars a year. Now, it receives more than $30 million a year in research funds.

Among the achievements of Kennedy Krieger’s researchers over the past three decades are the isolation of the gene causing Sturge-Weber syndrome, the development of treatments for leukodystrophy and muscular dystrophy, and the development of infant tests for autism, urea cycle disorders and adrenoleukodystrophy.

“Dr. Goldstein also made the fundamental decision to give up his own research and focus instead on the needs of the Institute,” adds Ann B. Moser, co-director of the Peroxisomal Diseases Laboratory at Kennedy Krieger and Johns Hopkins.

It was a tough decision to make, as Dr. Goldstein had trained—and had been practicing for some years, most recently at the University of Michigan’s medical center—as a pediatric neurologist. Other medical specialties, he’d found as a medical student, relied heavily on examining test results and X-rays, but with neurology, “you’re watching how a child walks, and you’re talking with the family to get the history and figure it out,” he says. He liked the person-centered nature of the field.

“It never crossed my mind to be a heart doctor or a surgeon,” he adds. “My skill set and personality just seemed best suited to pediatric neurology.”

A Culture That Permeates

Dr. Goldstein’s persistent dedication to improve children’s lives is deeply felt and shared by employees across the Institute.

“There’s a culture that really permeates this place, and it’s the commitment we all have to Kennedy Krieger’s mission,” Dr. Goldstein says. “It’s reflected at every level of the Institute, and it’s not because of me—it’s because of everyone here.”

As Howard B. Miller, a board member for the past 29 years and board chair for the past four, says, “We’re always thinking, ‘What do we need to do to make their lives better?’ It’s ingrained in everybody.”

“A lot of people have stayed here for decades,” adds Dr. Belcher, who’s worked at the Institute for 20 years, “because of this feeling, this esprit de corps.”

Today, scenes like a child walking for the first time after years in a wheelchair are not uncommon at all.

Every day brings new advances: A little girl smiles for the first time after severe psychological trauma. A teenager reads aloud with tears in his eyes because he’s never been able to read aloud before. Cheers erupt as a little boy regains consciousness and smiles at his family for the first time in months.

Things like this happen all the time at Kennedy Krieger—and thanks, in part, to Dr. Goldstein’s visionary leadership, they’ll continue to happen for decades to come.

Dr. Goldstein Farewell Video

Dr. Goldstein reflects on his 30 years at Kennedy Krieger, describing how he first came to the Institute, recalling memorable moments throughout his career and acknowledging the staff and faculty members who have helped turn Kennedy Krieger into the place it is today.