Research finds ADHD symptoms may result from diminished capacity for cerebral engagement

BALTIMORE, July 26, 2019 – A study published by Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology, found that children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may have differences in the parts of the brain that control movement.

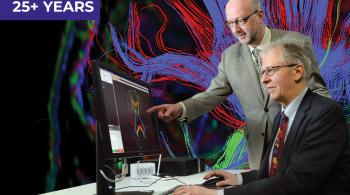

The study, conducted by Stewart H. Mostofsky, MD, director of the Center for Neurodevelopmental and Imaging Research at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, and Donald L. Gilbert, MD, MS, director of the Movement Disorder Clinic and Tourette's Syndrome Clinic at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, engaged 131 children ages 8-12 years old to identify brain-based measurements that could help detect different types of altered brain-pathways that contribute to ADHD. Of the group, 66 children had ADHD. Those taking stimulants for ADHD had their medication temporarily stopped, and those taking long-acting ADHD medicines were not included in the study.

Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), which stimulates nerve cells in the brain by placing a non-invasive device over the scalp, researchers were able to measure brain signals involved in controlling simple motor actions. This included engaging signals important for generating motor actions, as well as “braking” signals important for inhibiting motor actions. Using a race car game, the children were asked to complete an activity that required switching back and forth between moving, stopping and resting. This allowed the researchers to measure the brain’s ability to engage and inhibit motor signals under these different conditions.

“Focusing on the motor system, where we can simultaneously measure brain signals and associated motor behavior with a high degree of precision and detail, can help us discover reliable neurological markers of ADHD,” said Mostofsky. “This avenue of research could therefore support a “precision medicine” approach, leading to more targeted diagnosis and treatment for people with ADHD.”

The findings from the study revealed that, compared to children without ADHD, children with ADHD showed weaker ability to inhibit motor signals - both when moving and stopping, as well as at rest. In addition, the children with ADHD showed weaker ability to engage (up-modulate) motor signals when shifting from rest to moving and when shifting from rest to stopping. Importantly, Mostofsky and Gilbert also found that ADHD severity in children correlates with both weaker ability to inhibit motor signals and weaker ability to engage (up-modulate) motor signals from rest to task states. The findings suggest that ADHD symptoms may result from diminished capacity to efficiently and effectively harness brain signals important for selecting and optimizing how we respond to the world around us.

“Studies using TMS typically monitor the brain awake but at rest. Few groups have used TMS to study the brain while it’s engaged in specific activities,” said Gilbert. “This approach could be applied to many other situations involving emotions, behaviors and learning and to better understand what’s happening in kids with more severe symptoms that are not responding to treatments.”

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health (MH085328, MH078160, MH107719).

About Kennedy Krieger Institute:

Internationally recognized for improving the lives of children and adolescents with disorders and injuries of the brain, spinal cord and musculoskeletal system, Kennedy Krieger Institute in the greater Baltimore/Washington, D.C. region serves 24,000 individuals a year through inpatient and outpatient clinics, home and community services, and school-based programs. Kennedy Krieger provides a wide range of services for children with neurological issues, from mild to severe, and is home to a team of investigators who are contributing to the understanding of how disorders develop, while at the same time pioneering new interventions and methods of early diagnosis.

###